Diyarbakir: Housing the City. An interview with Martino Tattara [DOGMA] and Caglayan Ayhan-Day by Roberto Soundy

Quaderns #265

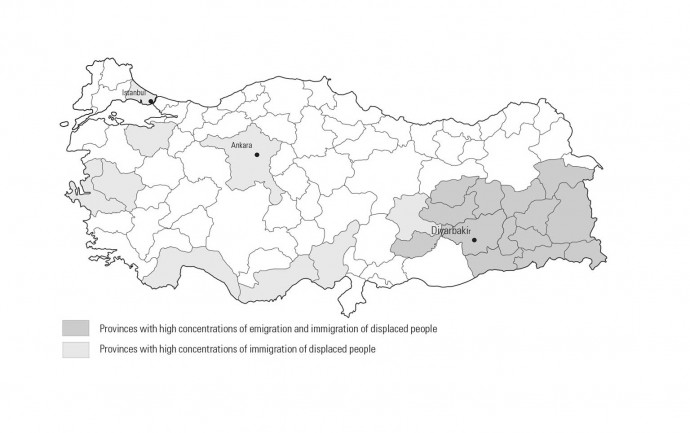

Diyarbakir is one of the largest cities in southeastern Turkey and is currently a divided city where the troubled political climate that has afflicted the region has had a dramatic effect on housing policies. In this interview, Martino Tattara, co-founder of DOGMA [with Pier Vittorio Aureli] and Caglayan Ayhan-Day talk with Roberto Soundy, from the Posconflicto Laboratory Productive Housing Programme, about the role of the architect in devising forms, tools and policies for large-scale housing solutions in order to relocate or regenerate the city’s deprived housing stock.

Roberto Soundy: When we think about a profoundly divided and disputed territory like Diyarbakir, displacement is the first thing that springs to mind. With over 3,000 villages destroyed, the social and political conflict that has pounded the region over the last thirty years has caused a deep gash in national and municipal policy on housing. In your opinion, what is the significance of housing and what are the possibilities for a project for the city in the face of conflict?

Martino Tattara and Caglayan Ayhan-Day: Everyone has a right to adequate housing and shelter. It does not matter whether you are in the middle of a conflict zone or a festival; everyone needs a safe house, a place to call home. However, especially during prolonged political conflicts, one sees whole settlements being evacuated, villages burned, civilians forced to relocate overnight, from rural to urban settlements, leaving their livelihoods behind, and left with only memories.

Diyarbakir, we wanted to bring international and local architects, academics, central government, local government, and local NGOs together around the same table, and get them to collaborate on how to provide adequate housing for the displaced communities who had been living in impoverished and unhealthy conditions – usually in squatter houses – in Diyarbakir. We thought that if we could incorporate the displaced communities into the project as arbitrators, to guide us regarding where to start, to tell us what they want, to review the work we have done, perhaps we could open a space for a therapeutic process of sorts.

After all, talking about buildings, gardens, courtyards and urban plans has the potential to be less confrontational and less biased than talking about imprisonment, ongoing conflict in the mountains, bans on the native language or unfair economic and social policies. Still, talking about housing can be equally productive: it juxtaposes stories about village and city, past and present, suffering and joy. So, we thought housing was a good place to start: it is an urgent need for the displaced communities living in squatter houses, and providing it is an indisputable obligation for the local and central government bodies. It is an academic and technical issue where professional expertise is required, and it is a social issue in which the experience and mediating role of NGOs are vital.

RS: Understanding the role of typology becomes critical, considering the continuous influx of forced rural migrations, especially since the 1990s. How can alternative forms of domestic architecture accommodate for the culturally disparate needs of the population?

MT/CA: Diyarbakir presents many challenges related with housing typologies and domestic architecture and their links to the needs and desires of the current population. Current housing production, whether the result of speculative real-estate forces or of the governmental agency for social housing [TOKI], is dominated by one unique ‘global’ model – a multi-apartment concrete block unit with approximately 10 to 15 floors – that in the case of Diyarbakir has monopolised housing development over the last decade or two. This typology has no relation with the traditional urban structure of the region – characterised by a dense pattern of narrow alleys and two-courtyard houses – nor with the local climate, characterised by extremely hot and long summers. Despite the poor construction and the poor climatic performances of these ‘modern’ units, this model still represents, for the majority of the population, the symbol of modern urban living. Proposing alternative forms of domestic architecture in Diyarbakir is therefore a social and anthropological challenge as well as an urban and architectural one. In our work, we approached the housing and domestic architecture project as inseparable from the possibility of changing the lives and livelihoods of affected people. We tried to understand the socioeconomic practices and living spaces of people in Diyarbakir, and we explored ways of opening up spaces of possibility within existing urban conditions. We also tried to emphasise that the conditions of Diyarbakir today have to be understood on their own terms, and dealt with as such.

RS: Beyond housing intended as a solution for offering higher living standards to a displaced and general population, the possibility of constructing a new idea of the city is at stake. What roles may national and municipal stakeholders, but also developers, NGOs and civil society play in questioning traditional modes of urban renewal?

MT/CA: The issue of urban renewal of the inner parts of Turkish cities is of paramount importance today, since TOKI has recently been assigned the new and urgent task of carrying out urban transformation projects all over Turkey, instead of just adding new, large-scale residential estates on the outskirts of Turkish cities. As many international cases have shown, and as many sociologists have already described, urban renewal often triggers processes of gentrification and displacement of the existing population living in certain parts of the city. In the case of Diyarbakir, the risk of gentrification is indeed present, especially in the ancient walled city – Suriçi, a neighbourhood with approximately 71,000 inhabitants – where land prices are currently greatly devalued and where speculative purchasing of land would begin as soon as there are any indications that the area might be improved.

Aerial picture of Suriçi. A large number of vacant parcels have become the location for the new proposed housing units.

With our project, we attempted to propose an alternative way of addressing the current urban landscape of the city, focusing on the potential of architecture to engage in both the economic and the social logic of the transformation process, striking a balance between investments for new middle-class enterprises and the potential that the current inhabitants could offer. This was particularly difficult as the current community moved into the neighbourhood during the migration waves of the last three decades and is not recognised by the city’s authorities as ‘autochthonous’. Indeed, for many local citizens, current inhabitants should simply be relocated to other parts of the city, leaving their houses and neighbourhoods for more prosperous, local, wealthy inhabitants. In order to counter this approach, we tried to show how it was especially this migrant population, with a rural background and view of life, that has been able to adapt to the older structures of the old city and its decaying courtyard houses. They established patterns of formal and informal economy and of solidarity that were directly linked to the urban and architectural form of this part of the city. Their self-built houses did not look as beautiful as their historical counterparts, and they may have further damaged some of the original structures in the historical houses they occupied. But it is also thanks to them that the old city is still socially very exciting and inviting. Thanks to them, the old city is still able to survive as a unique and lively habitat facilitating a specific mode of social solidarity and organisation.

Avoiding discussion on ‘origins’ and on whether someone has more ‘right’ to be a dweller in a certain part of the city than someone else, it seemed to us that triggering a new process of displacement would be devastating not only for those affected, but primarily for the neighbourhood and the process of renewal that is, especially in this case, associated with its preservation. This principle was and still is difficult to get across, and we feel that it is the task of NGOs and civil society initiatives – the most progressive component of Turkey – to question traditional modes of urban renewal before municipal and national stakeholders.

RS: As negotiations between the PKK [Kurdistan Workers' Party] and the Turkish government advance, the prospects of a negotiated settlement grow for Kurdish families separated by decades of conflict. Diyarbakir may yet again find another influx of inhabitants, only this time in the form of repatriation. In this respect, what purpose may local government policy represent in the social production of housing as a project?

MT/CA: It might be a little early to talk about such repatriation for the Kurds in Turkey. But if there will ever be an example of social housing being produced in Turkey, that will most likely take place in a city run by the Kurdish political party. Probably as a result of long years of political struggle and suffering, Kurds in Turkey have a unique passion, engagement and longing for a beautiful, peaceful and egalitarian urban and cultural environment. In cities run by the Kurdish political party in the Southeast and East of Turkey, the local governments seem to have a greater influence on public opinion and attitudes, and a more active role in creating a lively social and cultural urban environment. This is indeed a great advantage that facilitates the social and collective production of urban landscape.

However, housing projects take up a lot of time and resources for any local government. A local government determined to maximise public benefit rather than financial profit in urban planning policies would be taking great political and economic risks. But once local government’s resistance to undue urban profit is supported with actual examples of withheld building permits, increasing urban green areas right within the city centre and so on, this might slowly pave the way for a change in local people’s demands for different types of housing as well. If there are local incentives such as faster or less municipal paperwork for housing cooperatives that promise to build social facilities as part of their projects, if the municipality further develops a small scale multi-stakeholder partnership to set an example of such a collectively designed social housing project, then public opinion might also change towards developing multi-stakeholder partnerships, maximising social rather than economic urban capital.

In other words, we could also envision a situation in which powerful local governmental and nongovernmental actors have the upper hand in channelling desires related to urban landscape and planning. In such a situation, private interests, regardless of their economic capital, would be unable to sidestep local interests in their pursuit of accumulation and profit, and would have to devise and develop their projects bearing in mind the need to win the approval of a deeply democratic local governmental structure.

/// Martino Tattara and Caglayan Ayhan-Day led the research studio ‘Designing for Surici: Rethinking Urban Renewal.’ at The Berlage.

/// The large-scale strategic plan for Diyarbakir has been developed within the framework of the Berlage Institute research studio ‘After Displacement: Large-Scale Housing Solutions for Diyarbakir‘ led by Martino Tattara and Joachim Declerck.

/// This text is part of the research project Posconflicto Laboratory. The complete research material will be published in a forthcoming book with the same name.

![Una nova casa pati per a un emplaçament buit a Suriçi [projecte de Gabriel Cuéllar].](http://quaderns.coac.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/image_6-690x690.jpg)

![Una nova casa pati per a un emplaçament buit a Suriçi

[projecte de Gabriel Cuéllar].](http://quaderns.coac.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/image_6-220x220.jpg)