Hans Ulrich Obrist in Conversation with Kazuo Shinohara

Quaderns #265

Kazuo Shinohara [1925-2006] was a Japanese architect, educator and writer. Before practicing architecture he studied mathematics, which influenced his particular conception of architecture and the city. Between 1958 and 1978, Shinohara completed thirty-eight private residences, demonstrating nevertheless his ongoing interest in the relationship between the small scale of single-family houses and the conception of the whole city, also recurrent themes in Metabolism, towards which he maintained a critical stance in several respects. In this conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Shinohara explains his points of view on housing, the city, traditions and scale in both the Japanese and the European contexts.

[This is an extract from a series of interviews conducted by Hans Ulrich Obrist with Kazuo Shinohara.]

Hans Ulrich Obrist: In our last interview we discussed the “beauty of chaos” and “progressive anarchy”. This time around I’d like to ask you about the “mathematical city”. Designing a city generally involves all kinds of calculations and planning. But once built, it is very difficult to calibrate the city that exists. In this sense, the concept of the “mathematical city” sounds both paradoxical and extremely interesting.

Kazuo Shinohara: I majored in mathematics before studying architecture. Therefore, for me, thinking about mathematics is almost the same as thinking about architecture. It is like two sides of the same coin. I first started to talk about the “mathematical city” around 1967. At that time I had completed the House in White and my thinking was still deeply related to Japanese tradition. So, I started to say that the composition of a city should be based on the abstract and the neutral, which both include mathematical thinking. In short, I was now talking about something completely the opposite of Japanese tradition. These two directions are not in direct confrontation. But they do have an ambivalent relationship. The concept first provides a reason for small houses to exist; and then an opposing aspect emerges, so that the huge urban space of the city itself surfaces.

Until the 1960s, I had no direct experience in handling a city, and I said simply that the city could be left in chaos. In other words, we could only describe a city as an aesthetic of chaos. After that, I stated that the composition of a huge city could not be controlled without mathematics. It was impossible to achieve a real city composition by formal means, as was fashionable at the time. It was useless. And then, some ten or twenty years later on, chaos theory appeared in the field of mathematics. Therefore, my point of view, i.e. that the composition of a city has a complex mathematical nature, was given theoretical support by mathematical progress after a decade or two. Since chaos theory in mathematics was very new at the time, the rest of the architectural community reacted coldly during the 1970s and 1980s. Then, the theory suddenly became highly influential. My own vision, which I had stated around 1967, was perfectly synchronized with it. It was a mathematical approach positing that very state of confusion, or lack of unity, as its essential significance.

HUO: In your opinion, what is the ideal model for living?

KS: The central concept of modernism in the 20th century has been to unify. One of the concepts was an “international style”, by which architects tried to unify everything making use of its clarion principles. To take an extreme example, the Bauhaus even tried to coordinate table linens.

Now we’re approaching the 21st century and I am writing a series of articles, which say that the “un-unified” will assume superior value over humdrum unity. Restoring disjunction will become more important during the next century. After World War II, Tokyo had become a heap of ashes, and many progressive Japanese architects thought that they could completely transform it making use of Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin. They were dreaming. But I didn’t agree with their view. I stated that there is beauty in chaos. That was in the early 1960s, forty years ago. Nobody agreed with me, it was such an un-avant-garde idea for those times. The area surrounding Shibuya station was a typical example, with its sprawling, inconsistent, messy and natural conditions. But in fact, ten years later, a newspaper interview with younger people and foreign tourists asked them what they considered the most exciting area in Tokyo. Many answered, “Shibuya”. However, for progressive architects, Shibuya had always been one of the most ugly spots in Tokyo.

HUO: Could you tell us about your ideas of myth and chaos?

KS: In every myth, wherever it derives, there is a chaotic state. A great deal of energy is wasted. And, at first glance, that seems a negative loss. However upon reaching a certain level, it will be condensed into a powerful force. To achieve this, one must jettison all the force so far expended when this energy is sublated. What is created at that moment is a new first order. Take the example of an older period when ancient empire is the first order. But as this order gradually expands, it begins to break up. Then, a chaotic state starts to seek the next step. Through a repetition of confusion and conflict, the next order will appear. Thus, I can also say that chaos is a force or activity that advances toward the future. But, intentionally, I try not to use such words, because they sound too vague for what I want to convey. Anyway… although I do not know how the mechanism works, concentrated energy is actually converted into order whenever I introduce extraneous matter. The word “stimulation”, or “intervention”, might be better.

Interpreter: In scientific fields, and especially in complex systems, they use the word “emergence”, not “generation”, when describing something new. Your term is thus very close to science.

KS: I wanted nothing to do with the city when I was young, and that fact gives me a unique stance. But after working with smaller spaces that I tried to purify or to unify, I was able to take an opposite approach in my thinking. However, whatever I design, the world itself does not become beautiful. Formerly, I succeeded in generating opposition and I frankly stated my attitude as a “manifesto”. Since I examined our chaotic situation from an opposing point of view, by means of small houses, I gained an understanding of the structure of chaos. And I would like to add one more important point. I may design individual buildings but I am unable to design a city. In my opinion these are two completely separate things. People, culture, and climate generate cities. Not individuals. That was the biggest mistake made by Modernism.

HUO: What can you say about the self-organizing city?

KS: Oscar Niemeyer designed Brasilia as a very beautiful city, which is also well organized. At the same time, a slum area grew up, where the construction workers were living outside the designed area of the city. Soon after the city was completed, people began to prefer this older area to the new part because it was more comfortable. This is a typical example of what Modernism tried to eliminate. If a city becomes over orderly, you can always uncover an opposite and contradictory system. Therefore, there is clearly some other more complex structure of the city at work. Brasilia itself has a perfect design, but when a residential zone springs up alongside it, this latter is regarded as agglomerative or confusing. My idea is just the reverse. My small houses have a clear principle, whilst Tokyo is itself confusion. But we should be wary in construing the meaning of “confusion”, which isn’t the same as “disorder”.

HUO: When I talked with Cedric Price, he suggested that we use the word “city” too frequently and with so many different meanings that we are losing the original sense of the word. It becomes ever more blurred. So, it might be better to create a new term instead of “city”. If you have any good ideas, please tell me.

KS: I do not use the word “city” that much these days. In Japanese there is the notion of machi. I prefer this concept; it is closer to the term “neighborhood” or “district” in English.

HUO: What exactly is this notion?

KS: There are so many houses everywhere in Tokyo. And these houses will generate a street. The important point is that a street doesn’t generate houses. Houses make the street. So, to be more precise, machi implies houses producing the street as “house-scape” or as townscape.

HUO: Is that something organic?

KS: Well, for example, Europe’s older towns came into being naturally. And I do not know what the process was; a situation where houses stand beside each other as a matter of course is really something that just happens. This situation generates a street. In this sense, a street is no empty thing, in terms of figure and ground. Thus houses become the figures, so I prefer this view. That is why I use machi or “housescape”.

HUO: So is the line more important than the points?

KS: Rather, the façade line of the houses. I recall whole small villages I saw in southern Spain. In those little villages, the street seemed like a floor and the houses on either side like walls. I felt surrounded by white walls, and I liked that feeling very much.

HUO: You have written about chaos in the city, and at the same time you have influenced a couple of generations of architects when it comes to designing small urban houses. Would you tell me more about this?

KS: It is hugely important to understand the process of designing a tiny work. On the one hand, there are so many tall buildings around us, such as in Shinjuku, but they possess no power. Then there is the tiny house I constructed on a small budget making use of inexpensive materials, and somehow this tiny house exerts influence. A French architect based in Bordeaux who had seen this House in Uehara published was so impressed that she came all the way to Japan to study it. I perform experiments within a tiny space. I put extraneous elements into that tiny space to see what will happen. It is like a scientific experiment, and it is great because you can follow the process visually. It’s like the theory of elementary particles in physics, where a particle reflects the structure of the whole world.

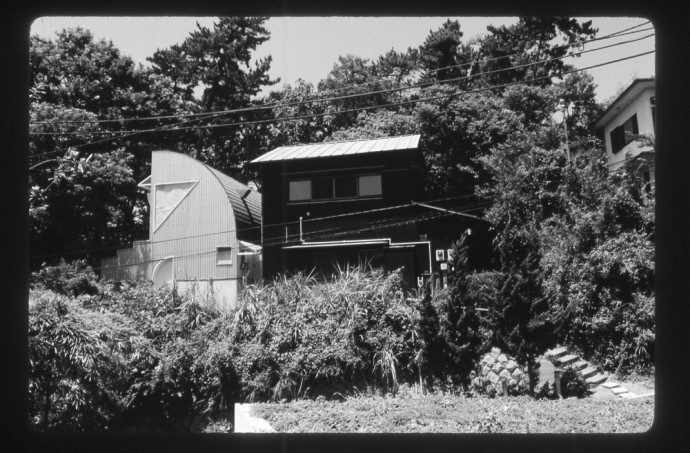

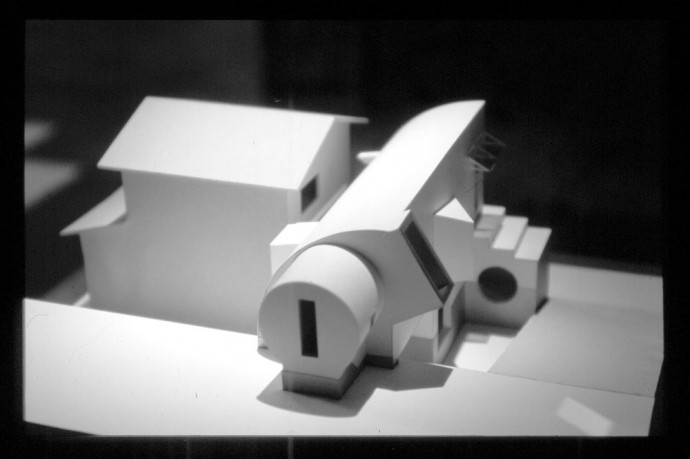

/// Header image: House in Yokohama by Kazuo Shinohara [model]. Photo by Enric Massip-Bosch.

Special thanks to Enric Massip-Bosch for his wonderful contribution with the photographs of Kazuo Shinohara, Office and own house in Yokohama, 1984.

/// More info about the work of Kazuo Shinohara can be found in the latest issue of JA+U, Kazuo Shinohara Complete Works in Original Publications.