‘The Empty Spaces of the Participatory City.’ Nuria Alabao and Rubén Martínez

Quaderns #266

Two young girls with pleated skirts and plaited hair play in a circle of sand containing a rectilinear seesaw. A month ago, this play area along with other playground structures around it was occupied by a huge mountain of debris from a bombed building. We are in post-war Amsterdam in 1947. From that year until the late 1970s – as part of a municipal programme – Aldo Van Eyck would imagine and construct over seven hundred parks in shady infill spaces, on corners in suburbs, ruinous plots of land and yards of all kinds. Spaces whose location was picked out by the inhabitants themselves in each of the neighbourhoods.

***

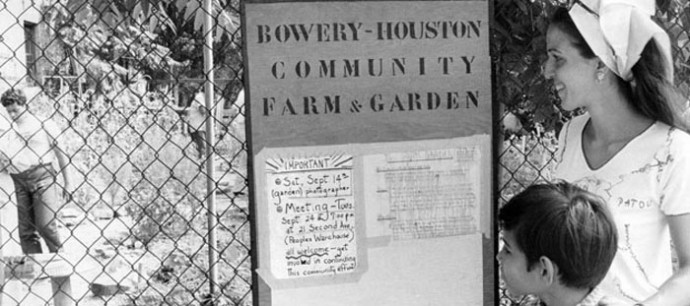

Tomatoes shine in the sun and, already ripe, are picked effortlessly by an elderly lady in a white hat. The vegetable patch covers a large part of the plot. To one side, a group of people of all ages chat on benches built from demolition remains. This is Manhattan, on a summer’s day in 1973. The oil crisis is battering New York. Social conflict is constantly increasing in certain areas as real estate activity declines. From that year up to today, Guerrilla Gardens have occupied hundreds of empty plots in the city.

***

A white dome covers wooden tiered seating where, in the shade, a group of people listen to a talk about biofuels. Outside, a few people are cooking on a barbecue as they chat. Children run. Somebody turns over the soil to start sowing seeds in a corner of the plot, which until recently was empty and walled. We are in Barcelona one day in 2015. The place is not managed and equipped by the local authorities as in the case of Van Eyck’s parks, nor has it been occupied and then legalised owing to pressure from the local community like many of the New York vegetable gardens; in contrast, it is the result of a public programme by the City Council that temporarily allocates these plots to neighbourhood organizations. This programme, run by the Urban Area Participation Department of Barcelona City Council and known as the BUITS Plan,[1] selects unused urban plots and, via public competition, offers them for temporary management by the local community.

***

The playground at Laurierstraat, Amsterdam in the 1960s, one of the 700 that Aldo van Eyck designed for the city. (Photo: © Ed Suister, courtesy Amsterdam City Archives)

These three images serve to conjure up a storyline: a storyline of plots of land, urban policies and community management.

Following World War II, the social consensus represented by the Welfare State implied that the public institutions would take charge of mitigating inequalities through a certain degree of planning and redistribution. This could represent the construction of public parks such as those designed by Van Eyck, or the building of subsidised housing that fuelled the modern movement. During those golden years of town planning and urban utopias, this movement would opt to respond to human needs through a social architecture financed using public funds. It is important to remember that the Keynesian consensus sought to apply brakes to the expansion of communism, which had also carried out its own experiments in political architecture.[2]

In capitalist cities, beyond or rather along the side-lines of urban planning development of a speculative nature, spaces for shared use will have to be fought for by the communities as in the case of the neighbourhood occupations of New York’s Guerrilla Gardens. During the 1970s, the oil crisis paralyzed the real estate market and left countless plots of land empty and lives broken due to unemployment and poverty. That same crisis represented the breaking point of the post-war consensus and marked the progressive decadence of the Welfare State as a form of government and of social conflict in developed countries. It was a narrative that would be substituted by another that justified reducing to a minimum any state intervention advocated by the neoliberal order. From that decade on, architecture would never again express public values, only those of the private sector.[3]

We return to the present, to a Barcelona that is a pioneer in metropolitan branding policies – its own brand being its Universal Forum of Cultures of 2004. At this moment in time, a new crisis in Europe is at the root of growing social mobilisation, especially in the south, where it is unlikely that a new Keynesianism would be able to tackle the catastrophes caused by financialized capitalism and its speculative bubbles and tax havens, which make even distribution impossible. So, what new narratives will be necessary to prop up the next model that will emerge from this frontier that we are undoubtedly crossing today?

With respect to city government, the great narrative is that of the smart city, where opting for the public promotion of a technologized city – although articulated hand in hand with the private sector – fits in poorly with a policy of reduction in public spending. Undoubtedly today – less visible, but no less important for understanding the future of urban life – new mechanisms for the management of the public arena are emerging.

A “social” capitalism

The proposal of the BUITS Plan based on management by the local community of unused spaces is a response to a historical demand by the city’s neighbourhood movement that fits in well with the policies of cuts in public spending and the slowdown in the real estate sector. Given the State’s incapacity to productively activate spaces in the city that have momentarily lost value and to provide for the basic needs of all citizens – social rights, conquered through struggles that lasted over a century and today are in danger – this institutional experiment aims to test a new management model. One in which the social fabric, always active to protect life, can be redirected towards solving what is contemplated as a passing problem of public management, barely a parenthesis, which is the reason for the temporary duration of the concessions. It is what the City Council’s programme head, Laia Torras, has dubbed “meanwhile management”.

We can say that these new discourses appeal to mixed forms between the artistic subjectivity of the post-Fordist creative classes and a certain social awareness activated as a market niche of unsatisfied social needs.[4]

To put it a little more clearly: self-management has always existed in modern society, from workers’ cooperatives and their networks of mutual support to squatting, whether the properties being occupied are buildings or urban or rural lands. But it is only now that these practices are being institutionally guided towards conversion into an added economic and productive space. Seemingly corresponding with this type of mechanism are policies such as the BUITS Plan, where architects who are out of work due to the crisis – and qualified middle classes or former middle classes – are linked with residents who need spaces for community life but also cheap leisure and consumer goods. What could be an inter-class alliance to reconquer the public arena, suddenly behaves like mutual exploitation.

Taller Verical, Pla BUITS, 2013. Photo: Re-Cooperar

Social management and social innovation

It is no coincidence that these kinds of community experiences are starting to be called “social innovation experiments”, a rhetoric encouraged by the most prominent new think tanks, the true hinge of the smart city that is connecting social creativity with the private arena capable of extracting its value.

One example could be the Barcelona Open Challenge, a Barcelona City Council competition held in 2014. A call to “entrepreneurs” designed to “transform the public space and the city’s services” that focused on the concepts of social innovation and entrepreneurship as the driving forces of production. The underlying message in this kind of programme is that responses to social demands have to pass through public-private partnerships that can be sustained by social creativity and the community networks that inhabit a devalued urban territory.

In these discourses there will be no more talk of social rights, but of challenges that small-scale private initiatives may resolve, one of the keys behind why it is so interesting today to promote social innovation on a European scale.[5]

Faced with the legitimacy crisis facing the State, who better than citizens themselves to design public services? Faced with the financial crisis and the lack of public liquidity, what public service comes at a lower cost than that undertaken by the social organisations themselves? Faced with generalised unemployment, might entrepreneurship not be a possible solution?

No more talking about collective rights, but about individual work challenges. No more social redistribution, but personal contributions by entrepreneurs. The dispossessing of social rights creates an unattended space that opens up a pathway to a more “social” market: rights as a market niche. A strategy promoted by the European institutions whose objective is to change the apparently unfeasible Welfare State for a “participatory society”[6] better adapted to the new times: that represented by programmes such as the BUITS Plan and the Barcelona Open Challenge.

Crisis cycles bring with them profound institutional changes. Although past cycles can help us to understand the present, nothing can be automatically taken for granted in these processes of regeneration. The quality of the institutional forms of each era is not produced by any think tank, but is socially constructed. Community self-management of plots of land or collective action relating to rights prefigure a new kind of institutionality. An institutionality that points towards both the orthopaedic designing of free-rider mentalities and to a scenario of democratic revolution. Nothing is written in stone about it being one thing or another, nor does it seem to depend on the number of public concessions that are on their way. The tonnes of community resources invested in self-managed plots plus the solidarity that forges urban movements are not a fixed capital for social entrepreneurs, but the apparatus that may just lead us to storming and taking heaven by force.

—Nuria Alabao, journalist and a PhD in Social Anthropology from the University of Barcelona. She has a degree in Information Science from the University Pompeu Fabra. She is currently researching on youngsters, Internet and politics as part of The Institut de Govern i Polítiques Publiques (IGOP) of the Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB).

—Rubén Martínez, specializes in the relationship between social innovation practices, public policies and new EU economies. He is co-author of the books Innovación en cultura: una genealogía crítica de los usos del concepto; and Jóvenes, internet y política, among others. Member of the Metropolitan Observatory of Barcelona.

—–

[1] Buits Urbans amb Implicació Social i Territorial (Urban Voids with Territorial and Social Implications). More information on the programme’s website: http://bcn.cat/habitaturba/plabuits

[2] If Le Corbusier perfectly expresses that Keynesianism in his “machines for living”, the Russian Ginzburg from whom he took inspiration is not just an architect committed to the Soviet Revolution, but his Narkomfin building aims to contribute towards encouraging a more community-based way of life, including spaces for collective life in the home. Two poles of architectural geopolitics connected by the thread of state intervention.

[3] Koolhas, Rem (2014) My thoughts on the smart city. Digital Agenda for Europe.

[4] For an analysis of the centrality of certain socio-economic profiles in the leadership of these processes see “la innovación social es de clase media” (social innovation is middle class) http://www.nativa.cat/2014/10/la-innovacion-social-es-de-clase-media/

[5] In search of a more in-depth analysis of these hypotheses, Rubén Martínez (co-author of this text) is currently working on an investigation into the promotion of social innovation policies in Barcelona and Madrid. Some texts written in relation to this research can be read at: http://leyseca.net/category/innovacion-social/

[6] Subirats, Joan (2013) ¿Del Estado de bienestar a la sociedad participativa? El País.