‘The Artificial Paradises of Studio Mumbai,’ Pedro Levi Bismarck

What is at stake for the post moderns is successful new designs for liveable, immune relationships, and these are precisely what can and will develop anew in ‘societies’ with permeable walls – albeit, as has always been the case, not among all and not for all.

— Peter Sloterdijk, ‘In the World Interior of Capital.’

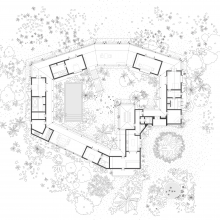

Studio Mumbai, house Copper II

Studio Mumbai, “Emotional architecture and architecture of proximity” [1]

Bijoy Jain of Studio Mumbai was in Porto’s Forum of the Future, last November, as part of the 2015 edition on the topic of Happiness. The Mumbai-based office has gained increasing visibility within the architectural scene of the past few years. This is largely due to a commitment to the use of artisanal materials and construction techniques, and to a discourse that advocates a sense of emotion and proximity with nature and place in an attempt to escape the “normativity imposed by globalization” (as can be read in the presentation brochure). Tradition, modernity, nature, landscape, are keywords of Jain’s lexicon, who graduated from the University of St. Louis, USA, in 1990, and whose career passed through Los Angeles and London before settling in India, where most of his built work is located.

Bijoy Jain’s presentation was consistent with his ethos. Following the modus operandi of many current architectural presentations, Jain entwined images of his personal cabinet of curiosities with photographs of his oeuvre. He devoted special attention to the description of construction details and traditional techniques, often emphasizing the work of artisans on site and evoking an overall harmonious relation between materials, techniques, architect, artisans and nature.

In a world where architecture is being increasingly afflicted by pure techno-logistical automatism and empty prêt-à-porter formalistic experimentations, Studio Mumbai seems to offer that last glimmer of hope and dignity that appears to have abandoned the discipline once and for all. It is thus not by chance that in a recent exhibition catalogue by the Canadian Center for Architecture – entitled Rooms You May Have Missed: Umberto Riva, Bijoy Jain, edited by Mirko Zardini – one can read that Studio Mumbai “proposes an alternative means of production for contemporary architecture and role for the architect in the economy of building”. However, it is precisely within this elated note of glorification that disturbing signs emerge to tarnish such an optimistic portrayal.

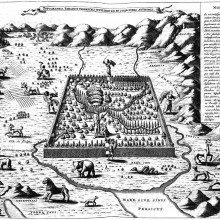

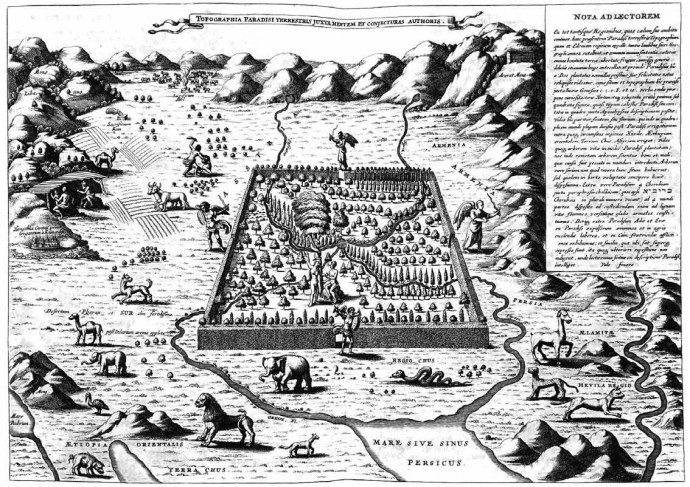

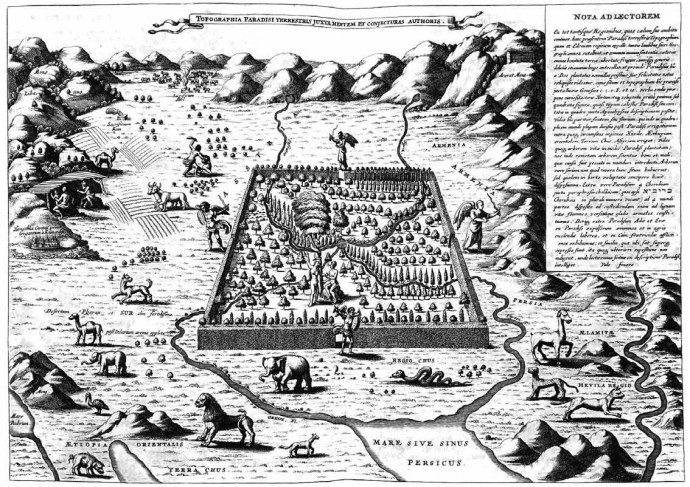

Athanasius Kircher, ‘Topographia Paradisi Terrestris’ (1675).

1. Artificial islands – nature, interiority, immunization

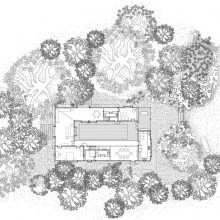

The first sign is the recurring appearance of the same type of program, the single-family house (notably generous regarding both dimensions and economy), but also the same kind of landscape, an exotic and wild piece of nature. Even in the case of their own office-house, located in a densely urbanized area of Mumbai, the city itself is presented in an aerial view taken at night, veiled in the quasi-poetic atmosphere of a soft mist (or is it smog?) that tempers the density, chaos and, most importantly, the disturbing inequalities that flourish in a megalopolis like Mumbai. These houses present a version of India that is absolutely idealized, stripped and disinvested of all the social and economic contradictions and discrepancies that dramatically affect and produce its everyday life and territory. [2]

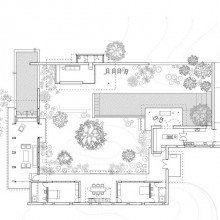

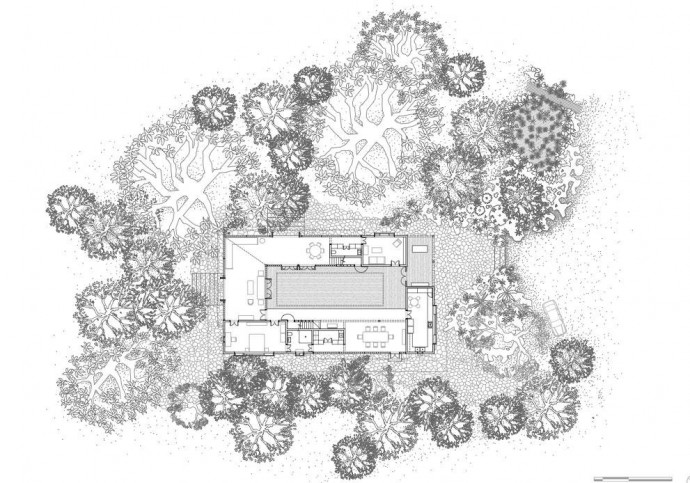

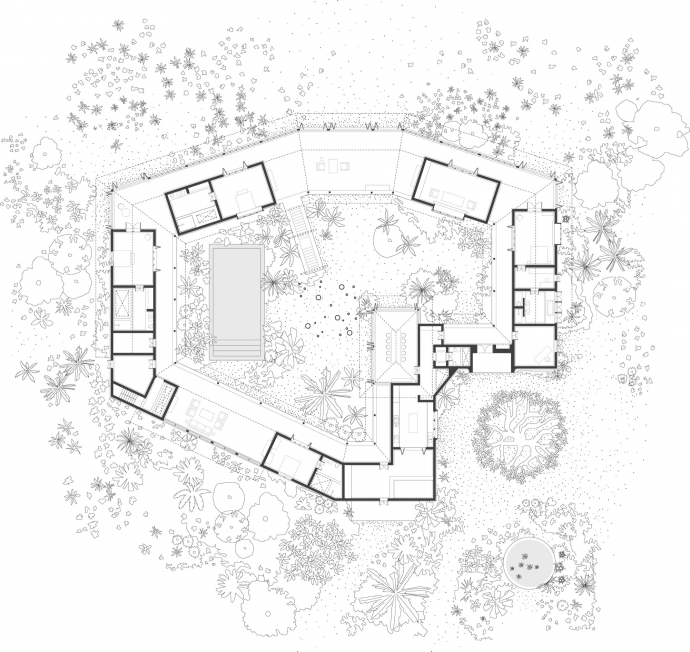

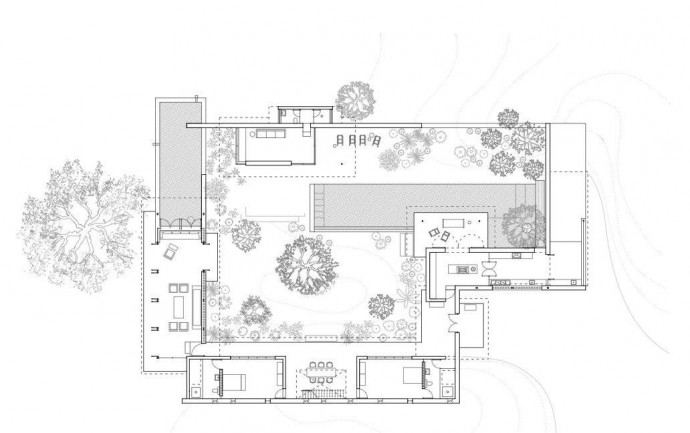

It is not by chance that these houses tend to fold inwards. They act as shelters that either open up to chase fragments of a mystified virgin nature, or enclose themselves inter muros seeking to recreate an original Eden, a miniaturized and idealized Earth like a hortus conclusus [3]. Therefore, contrary to what is being claimed, this is not an “architecture of proximity”, but rather an architecture of distance: it separates and detaches. Paradoxically – and this is Bijoy Jain’s magical touchstone – the effective apparatus of this detachment from the exterior is nature itself, or rather, nature converted into landscape.

The erasure of the exterior is not operated by walls and fences but by the large openings – windows and doors framing those miniature paradises or staging those nature-cloaks. But exteriority is not merely a question of opposition between outside and inside, nor is it simply a matter of genius loci; it is the social, political, and economical circumstance in which every house is de facto inscribed. Exteriority is a condition of togetherness, a relationship with otherness that belongs irreducibly to the human, shaping his sense of community, his own social self. It is not space that is a condition for the possibility of being together, but it is the being together that makes space possible.

The more idyllic this nature-as-landscape is, the more efficient the exorcising of exteriority becomes. But this architecture has no nostalgia for a return to pre-capitalist ideas of community (as in William Morris) or to a status of spontaneous and holistic relation with nature (as with Rudolph Schindler, to name a reference close to the Indian architect). These houses are neither “shelters from the bustle of the city”, in the euphemistic formula of Bijoy Jain, nor the hortus conclusus of a subject who retreats from the world in an act of resistance or exhaustion. They are artificial islands (a sort of singular family condos or gated communities) where fences and walls have been replaced by the eloquent nature-landscape apparatus, subtly detaching the houses from an exterior, which in the particular context of India assumes an especially problematic and disturbing condition.

These artificial islands are not enclaves of resistance against a specific logic of contemporary spatial production, they are softened cosmopolitan capsules, biospheric universes of highly connected networked individuals, artificial continents where an elite with high economic power finds a form of isolation and immunization from the processes of spatial production of which they are primarily responsible. They are systems of immunization that create an artificial, self-sufficient environment while minimizing all outside communication and simulating their own private public sphere. In line with Peter Sloterdijk, we can claim that these houses constitute themselves not only as “integral mechanisms of defense”, but also as “ignorance machines” where “the fundamental right of not-respecting the exterior world finds its architectural formula.”

Unsurprisingly, the reverse of these artificial continents – so cynically frugal – is the slum. The city of Mumbai – built over the years on landfills conquered from the sea – is itself an archipelago of artificial islands surrounded by the great ocean of slums. As always, the flip side of the “ecology of fantasy” is the “ecology of fear and violence”. And in any case, as Lieven de Cauter points out, “where fear and fantasy build artificial biospheres, the everyday is abolished”, immersed as it is in the lonely design of its own self-immunization and self-consumption.

Studio Mumbai, house Tara

2. Artisans, nostalgia, indigence

But there is a second sign, another crack in this Arcadian mise-en-scène: the employment of traditional processes and construction techniques comes with a condescending view of the artisan. The example presented by Jain in his conference in Porto of a woman at the building site transporting – “with such elegance” – a pile of bricks on her head, is a clear indication of this. In praising the gesture’s aesthetic and performative dimension one does not respect the artisan’s know-how – her techniques, modus operandi, authorship or social relevance – but simply romanticizes and fetishizes the condition of being-artisan. If, on the one hand, this approach may be helpful in calling for a lost harmonious relationship with labor – useful to challenge the automation and abstraction of large building sites – on the other hand, it does not do more than soften and naturalize the artisan’s framework of exploitation. Naturally, an entirely different situation would arise if the artisan were mobilized in a process where her emancipation (political and social) or that of her community’s would be at stake, for example, in the construction of a collective building where she would be contributing with work and knowledge and where the architect would act as a technical mediator of this process.

The act of romanticizing the artisan thus accomplishes the same function as the nature-landscape apparatus: if the latter softens the contrasts and inequalities of capitalist spatial production, the former, by sustaining the myth of original happiness in labor, naturalizes the artisan’s indigent social and economic condition, for, once finished the job, she has no choice but to return to the field of slums without qualities and to the eternal destiny reserved to her by the castes and capitalist economy.

Studio Mumbai, house Copper II

3. Studio Mumbai: “an alternative means of production for contemporary architecture”?

The fundamental matter here at stake is not to assess the aesthetic or technical quality of studio Mumbai’s work, but rather to attempt to deconstruct the current critical narrative that legitimizes this practice as “an alternative means of production for contemporary architecture”. Both the praising of traditional techniques and the idyllization of nature have been, for quite some time now, the impetus behind multiple architectural practices who appoint themselves a role of resistance against processes of globalization (for example, Peter Zumthor). This sensitive phenomenological discourse, endorsing a relationship with the world under the umbrella of sustainability and ecology, is particularly powerful because it addresses an essential gap in the relationship between humans and nature that has permeated modernity and globalized capitalist production of space.

But the real ambition of this kind of discourse is far from any real resistance, on the contrary, it fully integrates within the dominant logic of production. It frames our nostalgia for a lost paradise, an original Eden, and it dissimulates the problematic recurrence of a territory impregnated with social inequalities and violent processes of extraction-production-consumption. All the while, its success within the architectural field stems from the fact that it works as a fetish, a “stand in”, replacing that which one cannot have. It gives us the illusion of effectively attending to architecture’s real anxieties, and so it captivates many people: the increasing technocracy of architectural design, its empty formal experimentation, the absence of any content independent of the monetary-economical circuit, its conversion into a lifestyle commodity, its reduction to mere instrument of territorial logistics (from the exhausting icons of the Western world to the urbanizations sans rêve et sans merci in China and Dubai). In short, this kind of nostalgic discourse is the way through which architecture attempts to exorcize the ghosts of its immediate future without giving them, however, any effective solutions.

Architectural practices such as Studio Mumbai certainly produce beautiful images that easily populate our imaginary; they may even provide us with precious indications of how to apply local construction techniques, or they might suggest seductive conceptions of domestic space. But their relevance does not go further. They do not offer any hints, nor any tentative alternatives, nor do they even begin to state apprehensions regarding the role and task of architecture in the present condition. Contrary to what is stated, Studio Mumbai’s architecture does not offer an “alternative means of production for contemporary architecture”, it does not even critically address it. It only fetishizes nature and the vernacular, fully absorbing them into the endless circuit of neoliberal economy, efficiently converting the anxieties and fractures that it itself triggers into new business opportunities. What Studio Mumbai so blatantly displays in those “beautiful” houses is none other than paradise as commodity.

Studio Mumbai, house Utsav. Photography: Studio Mumbai Architects.

4. Towards a critical project and a project of criticism

Such an “alternative means of production” can never be found in an architecture that renounces to critically assess the territory where it is embedded, the space which it transforms and produces. The question begs for a deeper inquiry into the means, discourses and practices through which architecture can probe and challenge the prevailing processes of territorial production, the mechanisms at play (often violent), the forms of life and modes of existence at stake. Only by establishing a dialogue with this problematic exteriority can one hope to address such fundamental questions – the unstable bond between humans and nature and the revival of artisanal constructive techniques – beyond all fetishization.

In order for this to be possible one must challenge the autophagic consumption that now permeates the commonplace of disciplinary discourse: the cult of minute historical fait divers, the deification of authorship and its backstage creative mechanisms and details, as banal as they may be. In so doing, one must thereby overcome this apparent death in criticism (and its replacement by the curatorial and prize systems) by reviving and assembling both a critical project and a project of criticism.

Studio Mumbai, house in Pali Hill. Photography: Helene Binet.

Afterword. At home – in the inner space of the world – with no threshold

It is difficult to accept Studio Mumbai’s houses as models of reflection on contemporary dwelling. We should rather see them as expressions of a crisis of exteriority that currently afflicts the human. A crisis of experimentation with the world as such, an enclosure towards an outside beyond all culturally dominant mediations. These houses float like lonely commodities that serve the consumption of a voluntary self-immunization. They piercingly announce the ultimate rise of the space of immunitas and the corresponding dissolution of its counterpart: the space of communitas.[4]

If, in these houses, all limits seem dissolved that is solely because the entire exterior has already been interiorized. The threshold fades as an architectural element, losing its meaning and potential for openness, its role of in-between space, of liminal mediation and measure between the house and its exteriority, between the self and the other. That which lies beyond the house remains inside. What is at stake in this dissolution of limits (Gr. Peras) is above all the very dissolution of experience, of the house as experience, because, as the etymological root of the word indicates (Gr. Experientia, ex-per-ientia), there is no experience without a “going beyond”, towards an outside, without the crossing-confrontation of a boundary. Experience is always the experience of a limit, of an unknown. And a house is only a house so long as it achieves to be the place of this liminal experience of the outside – experimentation of the world, for the world.

Therefore, once again paraphrasing Sloterdijk, we can establish that these houses are the inversion of inhabiting: they do not install themselves in an environment, they install an environment of their own. «In this mode of experience the horizon is encountered not as boundary and transition to the outside, but rather as a frame to hold the inner world».

In consequence, we can claim that this is not an architecture of proximity as much as one of absolute distance: an architecture without other and without common. It lives simulated and dissimulated by a nature converted into reassuring and mystifying landscape, incapable of positioning itself in a critical and problematic relation with the surrounding territory. The atmosphere of timelessness in these houses is in no way innocent – they exist in a time that is not of this world. Without present, without past and, especially, without future. These houses are thus paradises from which all mankind has already been banished and from which no redemption can be expected. Finally, in the ultimate glorification of this architecture, the discipline consummates its own dissolution, confirming its absolute estrangement from a world that is now only bearable on the absolute condition of not being visible. “D’emporter le paradis d’un seul coup” [“To carry paradise at the first assault”] was the motto that French writer Charles Baudelaire invoked, rather ironically, in his Artificial Paradises.

—Pedro Levi Bismarck, architect and researcher on the Faculty of Architecture at the University of Porto. Editor of Punkto Magazine.

Translated by Bárbara Costa and Pedro Levi Bismarck.

—–

[1] “Emotional architecture and architecture of proximity”, was the title of the conference held by Bijoy Jain in Porto’s Forum of the Future, 5th November 2015.

[2] According to the World Bank, one third of world population living in poverty is in India: 400 million (30% of Indians), a number growing since 2007. India is a territory stratified and crossed so much by the system of castes as by capitalist processes of spatial production, giving shape to a space where social and economic inequalities are particularly visible.

[3] Expression used by the Indian architect echoing a certain zumthorian geist or spirit. Hortus conclusus was the title of the Serpentine Gallery summer pavilion designed by the Swiss architect in 2011.

[4] Roberto Esposito, Communitas. Origene e destino della comunità. Einaudi, 2006.