Aránzazu Melón: A saprophyte for Robin Hood Gardens and other phenomena

Quaderns #263

code: 26323

“At first sight, the wrecker resembles the saprophyte of the natural system, which reduces dead organisms to their simpler elements to speed the recycling of matter. But the likeness is only superficial. The saprophytes break an organization down into simpler compounds, in order to make use of the material and the energy released. Wreckers also break up old patterns, but they make little use of the energy released.”

Kevin Lynch, urban planner, 1990. (1)

The viewers of the British channel, Thames Television, voted in 1985, that the problematic local authority flats, Robin Hood Gardens and Trellick Tower, were the worst modern buildings in London. This vote is just one of the times in which popular rejection has been demonstrated towards Robin Hood Gardens, which is currently waiting to be demolished. The image of the deterioration of its concrete structure, which has never been maintained, but still valid, is joined to a certain prejudice of the British society towards the massive use of the concrete in housing blocks, which seems to reflect a more industrial recent past. On the other hand, Trellick Tower has been re-evaluated the London high-standing real estate market.

“The image idea is interesting, since from it arises the idea of knocking down. It is to the people who does not live there and to the council mayors to whom it is difficult to accept its presence.”

Druot, Lacaton and Vassal, architects, 2007. (2)

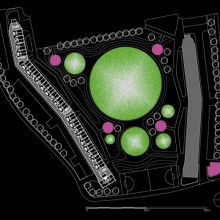

Robin Hood Gardens (1972), is a local authority housing scheme in Tower Hamlets, East London. It was built by the British architects Alison and Peter Smithson, in a lot, nearby the city’s financial centre, Canary Wharf, and the London 2012 Olympic Park. In March 2008, the local council announced the demolition of the 214 duplex flats in the existing urban complex as part of a new urban plan for the zone. The so-called “Blackwall Reach Regeneration Project” will see the building of 3000 new houses and facilities for the local community. Previously, the authorities felt that Robin Hood Gardens did not utilise enough architectural quality for its conservation. In addition, they argued that the investment of £70.000 per flat for the renovation would be too expensive. In 1963, Robin Hood Gardens had already been part of an urban plan that involved the demolition of the existing unhealthy terrace houses. So, paradoxically, in the 21st century, the urban development logic about demolition/reconstruction of urban residential fabric will repeat itself once again in this lot.

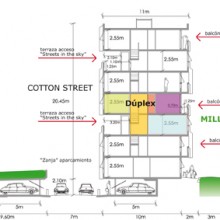

The problems of Robin Hood Gardens’ obsolescence are principally technological. Its lack of suitable maintenance and energy inefficiency adds the problem of overcrowding as a result of the numerous family groups. Nevertheless, from a typological point of view, the 214 duplex type flats of the urban complex have generous dimensions. Moreover, they are well distributed, illuminated and ventilated. Why is this potential wasted away?

The study Plus (2007) by the French architects, Druot, Lacaton and Vassal, demonstrates that the necessary budget for the demolition can be invested in a much more suitable way. The study suggests a constructive, typological and programmatic renovation of the existing flats and that in addition there is a potential for economical profit. However, European urbanism still follows the arguable logic prescribing a “do/undo” where it does not fit Rem Koolhaas’ concept, “Suspending Judgement”, which seeks to postpone a judgment to this type of architectures, like the 60s and 70s residentials, which seems that they lack sufficient value to invest in them.

It is necessary to indicate that a technological obsolescence implies the modernization of elevators, thermal and acoustic insulation. Functional obsolescence involves improvements in dimensions, distribution, orientation, densities and uses. What remains and what is destroyed to re-do? Other examples include:

The Balfron Tower (1965), was built by Ernö Goldfinger. A few meters from Robin Hood Gardens, there were 146 local authority flats. Though there are also problems of post-occupation, the building was catalogued and then it was sold with a refurbishment project that will invest £137.000 per flat and it will basically improve its thermal behaviour and it will provide new elevators. In spite of having technological obsolescence problems similar to those of Robin Hood Gardens, its heritage cataloguing prevents its elimination and the investment for its rehabilitation implies its repositioning within the real estate market. In London, other similar processes have already happened with other post-war local authority flats like the Trellick Tower (1972) and the Keeling House (1955), or the recently refurbished large urban complex of Sheffield Park’s Hill (Sheffield, 1960).

Across London, one can see that by the logic of urban contemporary planning of the European cities, the domestic and urban potential of many of the post-war local authority flats, technologically obsolete. This makes it difficult to invest in their refurbishment and to keep their status as local authority housing, which leads them to their elimination or their repositioning in the Real Estate market which is managed by its own laws.

What socioeconomic change would have to happen in order that this conceptual reversal does not take place in the current problem of access to affordable housing? It is possible to affirm that the sustainability need for the 21st century will necessarily imply an environmental efficiency of the existing buildings, and it will be an opportunity to restructure the construction sector, from an economic activity based on the production of new structures, towards an activity based on the re-use and transformation of the existing ones, producing habitability with low environmental impact. It has been demonstrated that to refurbish rather than demolish potentially valid structures, it can save up to 60 % in energetic resources.

“The rehabilitation can be a tool in the fight against the Climate Change, but it implies an adjustment of the economy towards a carbon free economy.”

Albert Cuchi, architect, 2010. (3)

1_ LYNCH, Kevin, Wasting Away – An Exploration of Waste: What It Is, How It Happens, Why We Fear It, How To Do It Well. Gustavo Gili, Barcelona 2005. p.92-93

2_ DRUOT, Frédéric, LACATON, Anne, VASSAL, Jean-Philippe, PLUS: Large Scale Housing Development – an Exceptional Case. Gustavo Gili, Barcelona, 2007.

3_CUCHI, Albert, Presentation in the ” International Congress on rehabilitation and sustainability. The future is possible ” in Barcelona on October 4th, 5th and 6th 2010.