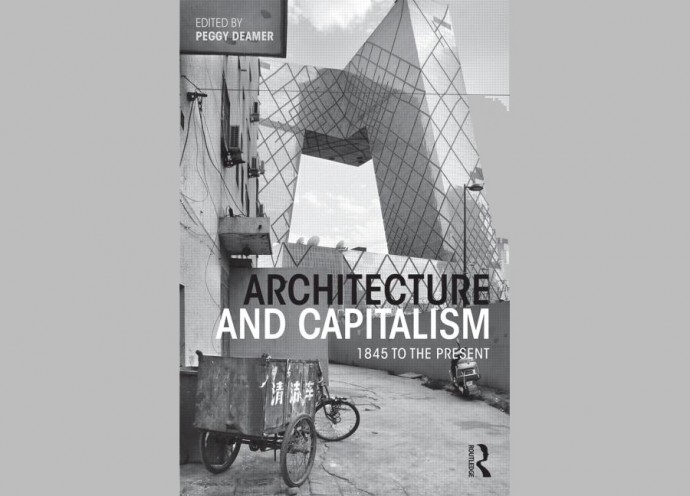

Architecture and Capitalism

Yesterday night Storefront for Art and Architecture hosted and event related with the book launch of Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present, edited by Peggy Deamer. The event was described as a forum, and described as follows:

“On the occasion of the book launch of ‘Architecture and Capitalism’ edited by Peggy Deamer, Storefront presented a forum where some of the book contributors and other leading figures in the discourse around politics, economy, architecture and the city presented and discussed some historical and contemporary references on how alternatives have been articulated in the past and how we might be able to articulate them today.”

We were lucky enough that our friend Ross Wolfe, author of The Charnel-House, attended to the event and send us the following review:

Last night’s book launch for Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present drew a large crowd to the Storefront for Art and Architecture in Lower Manhattan. The precise relation of the event to the newly-released Routledge collection was obscure, however. Of the four featured speakers —Thomas Angotti, Peggy Deamer, Quilian Riano, and Michael Sorkin— only Deamer and Sorkin contributed pieces to the volume. Deamer, the prime mover behind Architecture and Capitalism, wrote the introduction; Sorkin was responsible for its pithy four-page conclusion. Effectively bookending the discussion, then, the book’s themes entered into the conversation in a largely oblique fashion. For the most part, the talk was limited to generalities.

Some of the topics focused on by the speakers were fairly familiar, by now standard fare for reflections on architecture’s role in society. There was reference, of course, to the supremely compromised position of the architect within the existing system of capitalist reproduction. Given the present constraints encountered in the profession, Sorkin and Angotti pointed out, designers are typically bound to the whims of their clients. What little leverage can be mustered during the building process is usually a function of the “name recognition” of their firm. Otherwise, architects have very little say in how their visions are eventually realized, unless they stipulate specific guarantees beforehand [making it far more difficult to secure a contract in the first place]. If they don’t follow the instructions or meet the expectations of their employers, in most cases, all funding is cut off and the commission is lost. Questions concerning the supposed ethical obligations of the architect were also raised in this connection. Should architects refuse to lend their name to certain kinds of building projects? Prisons featuring cells for solitary confinement were listed by Sorkin as obvious examples, along with military installations with facilities built-in to serve as torture chambers. Deamer brought up the extraordinary conditions of exploitation suffered by the workers mobilized to construct, for instance, gleaming skyscrapers in Dubai. Not only the living labor involved in their assembly, Riano added somewhat vaguely, but also the dead labor embodied in the materials assembled.

Besides these scattered considerations, more theoretical issues of interpretation were also touched upon. Included here was some debate regarding the relationship between the material “base” of social production and the ideological “superstructure” it supports — that controversial architectural metaphor supplied by Marx over 150 years ago. While Sorkin dismissed this thought-figure out of hand as a vulgar Marxist holdover, Deamer interestingly suggested that there was an isomorphism that placed urbanism closer to the “base” and architecture closer to the “superstructure” in terms of the self-understanding of each field. Riano and Angotti rejected the notion of a stark separation between the two, pointing out that the two spheres often impinged upon one another, but failed to address the substance of Deamer’s contention. Though her argument could have probably been articulated more forcefully, Deamer did gesture in the direction of a key distinction between urbanism and architecture: a striving toward autonomy in the latter that is absent in the former. Urbanism deals more directly with the naked economic realities of real estate and the concentration of capital at the municipal level, despite entertaining some quaint delusions about its ability to act in the public interest. Architecture is closer to art in its pursuit of an autonomous ideal, although it requires marshaling significantly more resources to realize its object. There is more attention to form and abstract tectonic and stylistic considerations in architecture than city planning. Mention was also made of the building principles prioritized under neoliberal capitalism, as zoning laws seem predisposed to favor increasing property value for high-end real estate. Centrally located, spectacular design proposals receive preferential treatment as potential sites for capital accumulation. Sorkin repeatedly expressed dismay at architects’ propensity to “monetize air” by encouraging speculators to invest in costly buildings that will likely sit empty for years before seeing a return. To correct this corrosive trend, he recommended policy solutions that would reduce income inequality through a progressive tax and reform the building code to better serve the city’s inhabitants.

A few members of the audience could be seen squirming, however, as some of the panelists’ remarks were further specified. Stressing the importance of the utopian dimension in architecture as a way of thinking outside the limits imposed by capitalism, some slippage occurred in the terms used by the speakers. “Utopia,” one casually remarked, “is simply another name for what we used to call socialism.” Responding to this apparent parapraxis, someone from the audience challenged the discussants during Q&A: “Isn’t it possible that we might be able to work within capitalism to make the world less ugly? Couldn’t there just be a more beautiful capitalism?”

Thomas Wensing, a Dutch architect who was in attendance, quickly interjected: “They already have that. It’s called OMA.”

On the whole, the quality of the evening’s proceedings was wildly uneven. Without a doubt, Sorkin was the highlight of the event. He alone was able to distill the essence of the questions at hand and concisely formulate a response. Deamer was flatfooted and awkward throughout the majority of exchanges, and Riano seemed incapable of dealing other than in gross platitudes [including the cringe-inducing refrain that “all architecture is political”]. Even then, it is unclear whether the measures Sorkin was hinting at pointed beyond capitalism in any meaningful way. Consulting more architects and urbanists in policymaking decisions will hardly improve matters; in any case, capitalism cannot be designed away. For the very same reason, however, the decision of some architects to withdraw from objectionable ventures is unlikely to change what are by most accounts structural or systemic problems. At best, it might help them sleep at night. Perhaps the takeaway from all this is not that the panelists were simply tiptoeing around the task of giving an answer. What was more unsettling, in all probability, was the tacit recognition that the present impasse of architecture —as of society in general— no longer seems to elicit an immediately practicable answer. Toward the end, Angotti more or less said as much: “Back in the ’60s, or better yet the ’30s, when there was a real labor movement, we had a readymade answer to the question of what needed to be done. Nothing like this exists today.” This, and nothing else, was what was being avoided: not the question, but the lack of an answer.

—Ross Wolfe. Writer, critic, translator. Author of the forthcoming book, The Graveyard of Utopia: Soviet Urbanism and the Fate of the International Avant-Garde, scheduled to be published in the next few months by Zero Books.

/// More info: Architecture or/and Capitalism, Storefront for Art and Architecture.

/// Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present, edited by Peggy Deamer

UPDATE: This review has been responded by Quilian Riano on the post From Affirmations to Disruptions: Understanding Design as a Political Act and followed by Ross Wolfe on his own blog The Charnel House. For more updates about this interesting debate about architecture, capitalism and politics, you can follow @quilian, @rosswolfe and @Quaderns.