‘Mask. The Political Space behind the War on Terror.’ Marina Otero Verzier

Quaderns #266

The laundromat in my neighbourhood does something more than wash dirty laundry. It’s not a case of illegal goings on, quite the opposite. The workers at Bubbleworks, in New York’s Prospect Heights neighbourhood, contribute to safeguarding national security as they wash shirts.

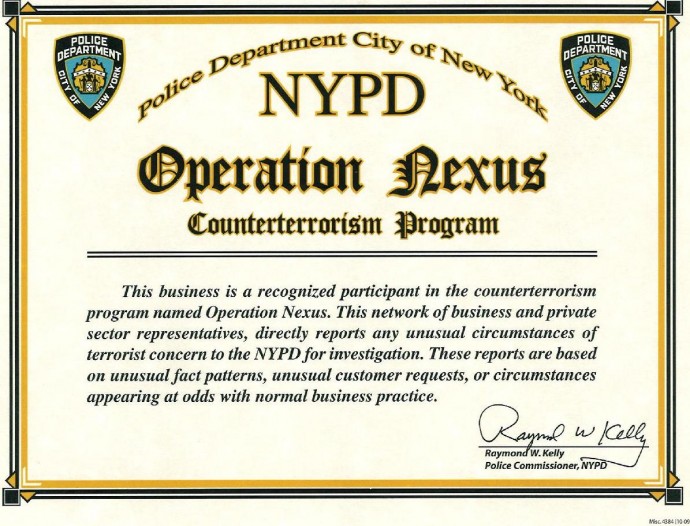

“You work in banking?”, asks the manager when I turn up there with six kilos of dirty clothes compressed into a bag advertising the country’s main financial institutions. “I don’t recognise your accent, where are you from?” With every transaction, he subjects me to a short interrogation. A year later he knows my address, telephone number and credit card number; my working times, my profession, the company I work for; my underwear, nationality, type of visa and my love life. Sometimes I discover myself dreaming about having my own washing machine. The other day, as I waited for him to return a couple of shirts to me, I looked at the framed certificates hung up behind the counter. “NYPD Operation Nexus” I read, “This business is a recognized participant in the counterterrorism program named Operation Nexus.” The manager, now back with the hangers, discovers me as I try to note it down. “So, you said you were an architect, didn’t you?”.

In 2012, as a consequence of 09/11, the New York Police Department established Operation Nexus, a nationwide network of businesses and enterprises, including everyday local businesses such as car parks, laundromats and stores, joining together with a common aim: the prevention of a new terrorist attack in the country. Since the launch of Operation Nexus, the police have visited over 30,000 establishments to encourage their owners and employees to use their professional experience to contribute to counterterrorism. For this, they are provided with a list of personalised protocols with which to identify “purchases, meetings or activities that may have connections with terrorism and to inform the authorities of them.[1] In exchange, they receive a framed certificate (like the one in my neighbourhood laundromat) and they become the first alert mechanism to protect the city of New York against another terrorist attack.

Back at home, while I do a quick search online for Operation Nexus, I think that perhaps, I ought to take my dirty washing elsewhere; I also think about how “security architecture” affects our relationship with the public space. In the last century, and especially in the present one, we have been witnesses to what Giorgio Agamben mentions in his book State of Exception as the “unprecedented generalisation of the paradigm of security as the normal technique of government”.[2] For the authorities, and equally for the manager at Bubbleworks, we are all a threat to the country, until proven otherwise. Observed online, at airports and also at laundromats, the security measures established to prevent terrorist attacks have converted the presumption of innocence into the presumption of guilt. Like many of the counterterrorism initiatives established since the start of the so-called War on Terror, Operation Nexus and its general framework known as Urban Shield make us all (and especially immigrants) suspects and, also, vigilantes –“Stay alert, and have a safe day”, reminds the voice on the New York subway in every journey.

The terrorist, according to the police, may be anyone who portrays themselves as “legitimate customers in order to buy or lease certain materials or equipment, or to undergo certain formalized training to acquire important skills or licences” which subsequently could be used to facilitate an attack.[3] In this process, as we are reminded by philosopher Étienne Balibar, the stranger is transformed into an enemy and is, all too often, subject to violent repression and institutional discrimination or, simply. to continued surveillance that is a threat to privacy and freedom of expression.[4] No, I don’t have anything to hide, but for months now I have been taking to Bubbleworks only what I cannot diligently wash by hand at the weekends. I understand the importance of protecting national security, but I prefer to feel like I’m under suspicion when collecting my underwear or when seeing what could be a friendly neighbourhood chat becomes a police mechanism for the extraction of information about citizens.

The laundromat example is, probably, the most banal example of how current unrestricted surveillance practices, the result of alliances between the public and private sectors and the economic and political goals that they serve, violate fundamental rights and undermine democracy. Compiling data does not necessarily have to be harmful, but we must pay attention to the power techniques at play, something that reminds us of the declaration signed by academics from all over the world against mass surveillance. spying. Through this letter they request that states effectively protect fundamental rights and freedoms and, in particular, our privacy. “It is protected by international treaties, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights”, they remind us, “without privacy, people cannot freely express their opinions or seek and receive information”.[5] And the fact is that counterterrorism tactics adopted by governments and the military place in evidence the violence inherent to the exercising of power and its capacity to undertake actions designed as much for our protection as the destruction of what makes possible our life in common, including our freedom and our political capacity.

Architecture participates in these processes. One could argue that the situation with respect to Bubbleworks would be resolved by having a washing machine at home. But in New York, their installation is often prohibited by contract and there are people who end up installing one illegally and emptying it via the bathtub. The question goes much deeper and the solution is not to change laundromat, but political action capable of articulating from legislation that regulates domestic architecture to technologies and “security architectures” that built the global “smart” city. The territory drawn up by the War on Terror is located at the intersection between physical and legal spaces, and it is characterised by the growing use of war technology and protocols in the civic space. Its “public security” apparatus tends to be managed by private interests.6 Within this context, sometimes I might forget that everyday I walk under the watchful eye of security cameras and urban surveillance systems, even interiorize the choreography drawn by my body – jacket and shoes off, hands behind my head – like the security checkpoints at airports. When talking on the phone, sending messages and using the social networks, my preferences and movements are stored in the cloud, where I share them with family and friends, and, i passing, with espionage programmes and data compilation companies. My habits are analysed by algorithms that classify me and by laundromat managers converted into police informers. Through a discursive operation, the institutions of power normalise this space of limbo between legality and illegality, law and violence, presenting it as an effective instrument in the fight against terrorism. Emergency becomes the rule and the city, a battlefield.

But if from the institutions of power legal and social hierarchies are being suspended to guarantee security, these measures are contested by opposing civic movements that employ technological innovations to construct spaces of freedom and political action: international networks of anonymous sources for the filtration of classified information; home-made drones that scrutinize the actions of the police; encryption systems for activists, journalists and humanitarian organizations; architectural designs with Faraday-type shields, or simply actions that range from covering the computer camera with a post-it, to refusing to pass through body scanners. This is the space in which our collective coexistence develops, the city as a great celebration of anomie.

In fact, as Agamben reminds us, the term iustitium – the technical designation of the state of exception – constructed like solstitium, means literally suspending the ius, the legal order, which connects the state of emergency with festival practices such as Carnival and other charivaric traditions.[7] “Anomic feasts dramatize this irreducible ambiguity of juridical systems and, at the same time, show that what is at stake in the dialectic between these two forces is the very relation between law and life.”[8] The anomic festival is, following this argument, the space in which we have a licence to suspend legal and social hierarchies and establish new orders, and in which it is possible to undertake “truly political” action, that which, as Agamben proposes, are capable of severing “the nexus between violence and law”.

I didn’t change laundromats. In a city like New York, you are grateful when people take an interest in you, call you by your name, ask you about your friends and family. When they miss you because you are on holiday. With every question, the Bubbleworks manager, in representation of the Administration, was protecting me against the dangers of terrorism while subjecting me to a legalised and standardised violence, structured by the logic of economic neoliberalism and masked behind an informal chat. Hours before leaving the city – and the country – I decided to make my last visit to the laundromat, this time to declare my right to privacy and the danger of surveillance programmes. And, deep down, to prove myself not guilty. When I entered I found my neighbour talking about how he had spent the weekend. I paid for the washing of the dirty laundry, took a photograph of the diploma, and said goodbye with a “see you soon”.

My next house will have a washing machine. Even if it has to be installed illegally.

—Marina Otero Verzier. Head of Research and Development, HNI. Chief Curator with the After Belonging Agency, OAT’16

—–

[1] Operation Nexus, Police Department City Of New York (NYPD), official website of the City of New York, [Consulted: 12-11-2014]. Available at: http://www.nyc.gov/html/nypd/html/crime_prevention/counterterrorism.shtml

[2] Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception, trad. Kevin Attell (Chicago y Londres: The University of Chicago Press, 2005), 12.

[3] Operation Nexus, Police Department City Of New York (NYPD), official website of the City of New York.

[4] See Étienne Balibar, “Strangers as Enemies, Walls All over the World, and How to Tear them Down”, lecture at Columbia University, 3 November 2011. Available at: https://www.francoangeli.it/Riviste/Scheda_Rivista.aspx?idArticolo=45634

[5] “Academics Against Mass Surveillance” [consultation: 4-1-2014]. Available at: http://www.academicsagainstsurveillance.net

[6] Judith Butler offers a reflection on the consequences of the militarization of the police force in the United States and the Urban Shield counterterrorism programme in her lecture “Human Shield”, given at the London School of Economics on 4 February 2015. Available at:

http://www.lse.ac.uk/newsAndMedia/videoAndAudio/channels/publicLecturesAndEvents/player.aspx?id=2859

[7] Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception, 41, 71.

[8] Ibid., 73.