From Affirmations to Disruptions: Understanding Design as a Political Act

A few days ago we published a review of Storefront for Art and Architecture’s event Architecture and/or Capitalism written by Ross Wolfe, who was able to attend to the round table and send us his points of view about the discussion held around the publication of the book Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present, edited by Peggy Deamer.

Following that review, we received a text that architect Quilian Riano wrote expanding on thoughts from the same event. Riano is a designer, researcher, writer, and educator currently working out of Brooklyn, New York; and founder of DSGN AGNC. This text can be understood as a response to Wolfe’s text and more important, it opens the discussion by sharing a different point of view and strengthens the conversation about issues so important in the current moment as capitalism, economy, politics and architecture. Here is Quilian Riano’s text:

“It has to be said that historically, the connection between capital and architecture has not been so mysterious; architects in the not so distant (European) past actually did build their practices around their overtly formulated economic positions.”

-From Peggy Deamer’s introduction to Architecture and Capitalism

Last week, during a public conversation at the Storefront for Art and Architecture for the book launch of Architecture and Capitalism, I said that “all design is a political act.” This made blogger Ross Wolfe cringe in an opinion piece about the event here in Quaderns. In his piece, Mr. Wolfe consistently ignores the context for the event and many of the remarks from that evening. I will, however, take this as an opportunity to give just such context to my remarks and expand on what I meant.

First, I invite everyone to see the entire discussion online and to read a short post I wrote after the event summarizing and expanding on my thoughts, here on Architecture and/or Capitalism Conversation.

The discussion began with moderator Peggy Deamer bringing up a claim she made in the book regarding the Marxist distinction between superstructure and base. In the introduction, she claims that architecture primarily functions in the superstructure, in the “realm of culture, allowing capital to do its work without its effects being scrutinized.” In the conversation, she posed the question of whether urbanism, because of its more clear ties to the economy, resides more in the base. All panelists promptly dismissed the binary as unhelpful and perhaps even dangerous. As part of my response, I stated that is important to keep in mind that both architectural and urban form are the result of political and economic forces.

As we continued to discuss that statement, it became clear that we were all troubled by how the role of capital is almost completely obscured in architectural practice. In architectural offices, designers make decisions every day while ignoring potential political consequences, such as labor conditions and environmental impacts. We then talked about the need to confront this willful ignorance.

When I said that all design is a political act, I meant it both as a statement and as a question to provoke further discussion. Why is it important to state such a seemingly obvious point? Because architecture is not often discussed that way, especially in academia or in practice. I often go to reviews where students and faculty only discuss the formal aspects of projects, ignoring all social and political conditions produced by or enabling the work. This is in part because the post-functionalist ideas popularized by Peter Eisenman are now the predominant ideology of architecture schools, especially in the U.S. This ideology claims that architecture should only work within formal discourses, rejecting any political discourse in what can be seen as an over-reaction to the failure of heroically humanist discourses of the late-modernist period. Eisenman has gone as far as to claim that “Liberal Views Have Never Built Anything of any Value.” These views are so ingrained in the field that even emerging practitioners espouse them as given truths as seen in a recent interview with Jimenez Lai who said: “When people talk about being more than just architects, about solving other world problems —affordable housing, carbon emission, landscape urbanism—in my mind, they’re effectively forfeiting the very thing they’re supposed to be an expert on. If we’re not going to cultivate formalism, who will?”

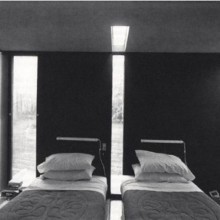

Image of a Peter Eisenman-designed house with glass slot in the center of the wall continuing through the floor that divides the room in half, forcing there to be separate beds on either side of the room so that the couple was forced to sleep apart from each other. ArchDaily

Furthermore, most often professors and practitioners who talk about larger political processes at all do it with the ironic detachment that has at times has been the modus operandi of one of the most prominent architectural practices, Rem Koolhaas’ Office for Metropolitan Architecture. In fact, one of my favorite essays in Architecture and Capitalism is “Irrational Exuberance: Rem Koolhaas and the 1990’s” by Ellen Dunham-Jones — you can read an excerpt of it in Places Journal. In the essay, Dunham-Jones says the following about Koolhaas’ ironic flirtation with capitalism:

“Nonetheless, over the decade, his writings and designs contributed significantly to shifting design discourse away from critical theory toward post-critical, non-judgmental research, and from autonomy toward engagement — albeit engagement largely with the elite beneficiaries of the New Economy, now often described as “the 1%.” From our contemporary perspective, it is thus worth asking: What is Koolhaas’s legacy vis-à-vis progressive practice?” (Page 151)

In the current context of architectural production, politics are either ignored and not thought to be important for form-making or referred to ironically, without any real consequence.

What I am concerned with is ways in which we can begin to ask political questions in architectural studios in academia and practice. I will posit that the first step is a reaffirmation that all architecture formalizes invisible forces and ideologies. A similar sentiment was expressed humorously and concisely by Slavoj Zizek in a Vice interview. In discussing postmodern companies and bosses that try to hide their power by dressing and acting casually, Zizek says that “the first step to liberation is to force him[/her] to act like a boss. Stop acting like a friend and give me orders.” Similarly, one of the first steps we need to take towards liberation is to recognize capital’s power lest one get seduced by the seemingly casual air of boutique architectural practices and tactical urbanism salons. Only then can we begin to have a conversation on how architecture can begin to formulate alternatives.

Presently architects who ask questions of the role of capital are labeled as political or activist architects. These monikers obscure the fact that we are all involved in the complex capitalist processes that produce a building, a space, a city. No one producing form can claim innocence.

Do we then need to stop practicing as architects? No!

Recognizing that current architectural practice is inextricable from capitalist processes can inject political discourse back into the discipline. Many architects, artists and designers are beginning practices that reject unrealizable utopianism and instead take on existing systems of power. These practices seek to understand and illuminate systems of power in order to change them. A project that attempts to enact such change, from outside of architecture, is Strike Debt! a project started by artists that effectively intervenes in the U.S. debt system.

This project points towards the potential of designing actions that are intentionally shaped by political forces and in turn are designed to push back on those forces. The Storefront was filled to capacity for this event, showing that architects, in fact, want to engage in critical political discourses. Perhaps this also signalled a clear dissatisfaction with the notion that we can do nothing in the face of a complex global capitalist system. A reaction against the notion that we cannot act critically on the city. There may be a time for a more fully utopian moment — for a revolution —but for now we can use design to illuminate systems of power and strategically act on them.

—Quilian Riano. Designer, researcher, writer, and educator currently working out of Brooklyn, New York. Founder and principal at DSGN AGNC. Masters of Architecture at Harvard University Graduate School of Design and Bachelors of Design (Summa Cum Laude) at the University of Florida, School of Architecture.

/// Header image courtesy of the Storefront for Art and Architecture

/// More info: Architecture or/and Capitalism, Storefront for Art and Architecture.

/// Architecture and Capitalism: 1845 to the Present, edited by Peggy Deamer

Great article but It could be difficult to read due to the use of typefaces

I was at the event and I have read the discussion with Ross Wolfe, but I have to agree with Ross that the statement that all architecture is political is too general. We all have to operate within (or push against) the limits of the current political and economic systems. If this complicity is acknowledged, then you can define your role as an actor within it. Just as a baker needs to bake bread to earn a living, an architect needs to design and build structures. Without seriously going into the notion of a paper / utopian architecture, I do think that the realm in which a discursive and political architecture can operate is therefore extremely limited. The underlying question is much larger; how do we put a political and financial structure in place which enables us to make more equitable environments.

As for the negative influence of Peter Eisenman, I think this may be a bit of an overstatement. In most European, Latin and Asian countries the influence of Eisenman has been extremely limited.

Thomas, I would say that to me this is the statement that is way too general as to become paralyzing rather than actionable:

“The underlying question is much larger; how do we put a political and financial structure in place which enables us to make more equitable environments.”

Yes, we all understand that the system needs to change. But at this point I am pretty confident that none of us has an answer on how or what it would look like after that change. This is also a weirdly classical-modernist (and Euro-centric) view of looking at the world. Once we erase everything what does the new look like? Are we sure it would be better or just another failed modern experiment? Are we to rethink all structures from scratch or is there room for revolution and reformation to happen simultaneously?

I will maintain that yours and Wolfe’s is a pessimistic and fatalist view. At the end this is all fine to discuss in academic circles, but I am an architect and I am not willing to make the false decision between: 1- choosing sconces for luxury clients 2- waiting until the entire system changes to “someone’s” revolutionary ideas or 3- retreating to paper-architecture or sci-fi as a pseudo-political act. I am not willing to wait for the revolution to later understand what those in charge of my new liberation want from me and what levels of purity in political thought they want.

I will work now with those that are doing something to create critical disruptions in the world right now. But this is not the “do anything” attitude that Zizek critiques in contemporary anarchists. This is a critical way of operating to create smart disruptions. This is highlighting systems of oppression, this is making proposals that can create real change while raising political consciousness. This also, by the way, includes talking clearly about existing racial/ethnic, gender and class privileges.

As for the Eisenman, I never said he was the only one working on the post-functional project — he is just a leading figure in the U.S. (a context that I know better). Actually, as we all know, this project really began in Europe. From my many work visits to Europe and Latin America architects there maintain a narrow definition of what it means to be an architect and what architecture can do, especially when it comes to critical political engagements. There are places where this may be changing like the many promising politico-architectural collectives coming out of Spain and Puerto Rico, or the work of dutch artist Jeanne Van Heeswijk but these remain the exception not the rule.

A longer response to Quilian’s article is linked above.

Regarding paralyzing vs. actionable judgments of the contemporary architectural situation: I would contend that ineffective action, by definition, is effectively equivalent to no action at all. Since the rise of “activism” in the 1960s antiwar movement and “direct action” following the alterglobalization protests, there’s been a prevailing attitude of contempt toward what is seen as “the paralysis of analysis.” The disdain for any theoretical reflection that does not lead straightaway to a positive practical program is, I believe, misplaced. Critical theory is not called upon to perform miracles, to see immediately workable or pragmatic solutions where none are actually to be found. What it can do, however, is articulate — through a ruthless critique of that which exists — the conditions that would be necessary for a revolutionary architecture to again become possible.

Nowhere have I argued that architects should pack up their bags or close up shop. Good architecture has been and continues to be made under capitalism, bringing real and occasionally enduring improvements to people’s lives. It would be foolish, however, to maintain that this is the primary function of even the best buildings or designs, considered at a systemic level. An individual architect’s intentions might be quite noble, in fact, but the extent to which his or her efforts can be realized under the present social order is determined by the totality of existing forces and relations that obtain at any given moment. Progressive architecture and design may be tolerated within certain prescribed limits, and broader allowances may be made for more ambitious projects or interventions in specific cases, but it would be a grave error to see the political impetus in such instances as arising out of architecture as such.

For example, should sufficient opposition arise within society to threaten the ordinary functioning and reproduction of capital, demands can be placed on governments that are much more likely to be met. Rosa Luxemburg argued over a century ago that the possibility of substantial legislative reforms was itself symptomatic of the danger (real or perceived) that revolution might take place. This would require a sustained, politically organized mass movement at the heart of capitalist production, concentrated in the most advanced centers of world industry. Needless to say, the center of gravity for such a movement would have to come from outside the narrow professional milieu of architects and urban planners. Of course this doesn’t preclude their involvement in such a movement, as workers and specialists from a wide range of professions would likely be involved.

In fact, this is what I took to be the essence of Thomas Angotti’s remark toward the end of the event. Without a viable working-class movement — through which architectural reforms might acquire political salience — answers are much harder to come by. Fears surrounding the potential consequences of revolution are no doubt real, and are indeed as old as revolutionary history itself. At least within the Marxist tradition, the point of such social and political transformation would not be to “erase everything,” as Riano puts it. This would amount to merely an “abstract negation,” the total annihilation of anything and everything in its path. Revolution in Marx’s sense, as Žižek would be keen to point out, would follow a more Hegelian logic of “determinate negation,” arising out of the conditions that presently obtain.

Dear Ross, I think the crux of this impasse between you and I is that you seem to narrowly define what critical theory and architecture are and can do. As a designer, I am willing to experiment and push on both, trying to expand what the two can do together.

In my previous responses I have pointed towards a few possible ways for design to work within critical theory so I will not go into it again.

I do like this:

“Without a viable working-class movement — through which architectural reforms might acquire political salience — answers are much harder to come by.”

I think we can agree that architects working in a revolutionary vacuum can only affect limited change. What I am arguing for, actually, is the critical role by which architects/designers can help create, support, maintain those movements.

Finally, during our twitter discussion Cesar Reyes reminded me of Keller Easterling’s excellent essay “out-maneuvered by stupidity’s agility” in “Did Someone Say Participate?” In that essay Easterling says the following about the potential role of architecture in the current political environment:

“Righteous political resistance, sure of its central principles, strangely resembles the righteous tautologies of stupidity itself. Righteousness even fuels stupidity’s tendency to symmetrical deadlock. Moreover, the principled stances of political resistance are out-maneuvered by stupidity’s agility with multiple fictions…

A resistance that protects authentic locality not only protects an impossible fiction in a world where capital is flowing in all directions, and sets up future targets for abuse…

In this light, tools like architecture and urbanism, which seem to be seen of political dealings, may be particularly well suited to send in a new technology or logistical wrinkle — one that tips the power of the lockdown towards other political contingencies. Resistance too may adopt stupidity’s agility to manipulate and confound the world’s most abusive situations – if it is too smart to be right.”

Again, the Keller Easterling quote — expanded/corrected:

“Righteous political resistance, sure of its central principles, strangely resembles the righteous tautologies of stupidity itself. Righteousness even fuels stupidity’s tendency to symmetrical deadlock. Moreover, the principled stances of political resistance are out-maneuvered by stupidity’s agility with multiple fictions. Certainly some of the classic powers associated with the proletariat apply to a worker who no longer exists. A resistance that protects authentic locality not only protects an impossible fiction in a world where capital is flowing in all directions, and sets up future targets for abuse. Yet just as the utopia of the park turns into its supposed opposite — a ubiquitous condition — so the state of political immunity and exception may turn into its opposite: resistance. Exception, as its alternately understood to mean a temporary or unique opportunity, can create both interior and exterior conditions that place the park in the crosshairs of the political conflict that it attempts to banish. These opportunities may be most effective not when they righteously and officially square up to the problem, but when they invent an ingenious ricochet that changes the terms of the situation.

In this light, tools like architecture and urbanism, which seem to be innocent of political dealings, may be particularly well suited to send in a new technology or logistical wrinkle — one that tips the power of the lockdown towards other political contingencies. Resistance too may adopt stupidity’s agility to manipulate and confound the world’s most abusive situations – if it is too smart to be right.”